Dog Tags: Identifying our Deceased Military Veterans

May 1, 2023 by Michael Strauss

Thanks to our special guest contributor Michael Strauss, an Accredited Genealogist from AncestryProGenealogists® for this informative article on military research using dog tags.

Behind the imposing gates of Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia rests the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier. Around the clock, active-duty personnel stand as sentinels remembering our fallen veterans. Many cemeteries have remains of soldiers from past wars marked with a single haunting word, “Unknown.” To properly identify each man and woman who have paid the ultimate price for their country, the military created identification tags. Here is a look at how those tags have changed over the years.

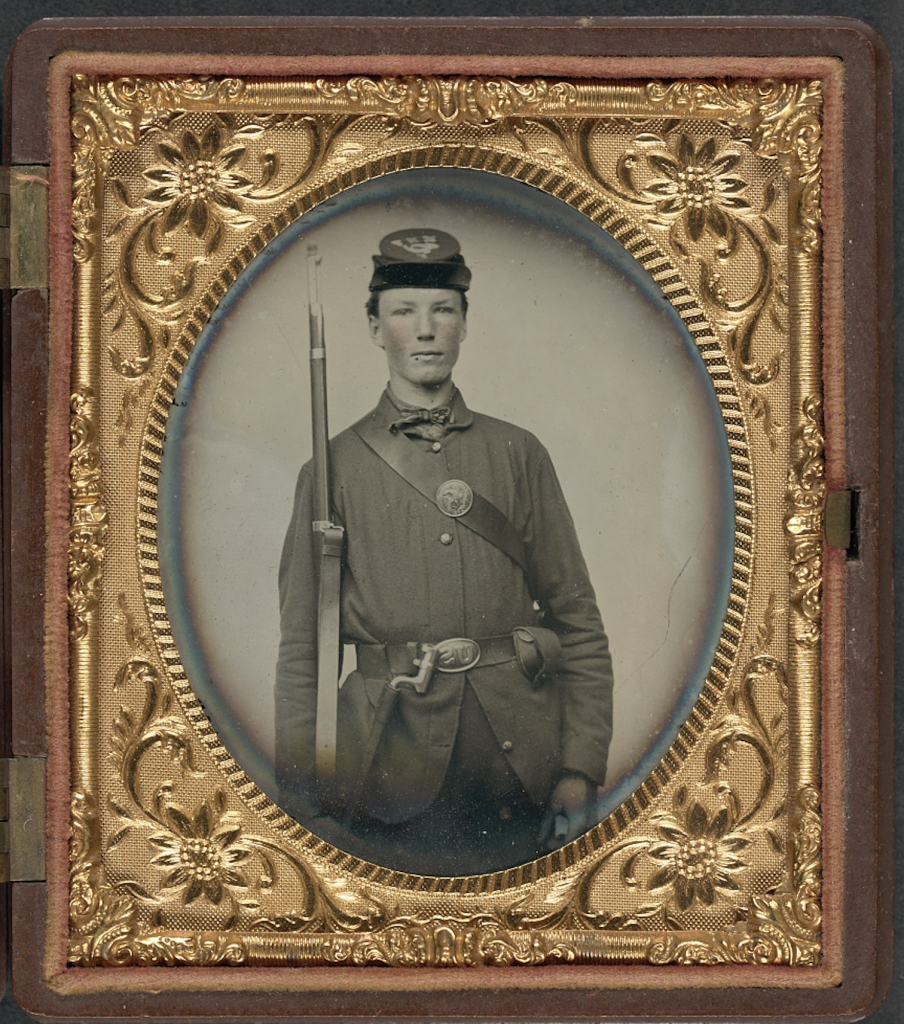

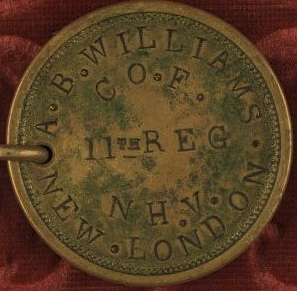

Civil War

The Civil War changed how military officials recorded battlefield deaths. On April 3, 1862, the Adjutant General Office (AGO) of the War Department issued General Order No. 33, which in effect read: “To secure as far as possible the decent internment of those who have fallen or may fall in battle…lay off lots of ground in a suitable spot near every battlefield and… register of each burial and will be preserved”.

During the Civil War, large numbers of casualties on both sides prompted soldiers and civilians to consider other ways to identify fallen soldiers. In 1862, New York City resident John Kennedy wrote to the Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton. He proposed that the US Army provide a medal identification badge for all officers and enlisted men that soldiers could wear under the clothing. The War Department rejected Kennedy’s proposal.

Civil War soldiers could purchase (at their own expense) identification badges or tags manufactured by military camp suppliers called sutlers. Sutlers were civilian contractors who travelled with the armies selling commonly needed items from photographs to wares. Some of these identification badges and tags were ornate in design.

Death became a reality for thousands of soldiers who had no proper identification. During the battle of Cold Harbor on June 3, 1864, soldiers, knowing they might be killed, wrote their names and military units on loose slips of paper, and pinned them to their kepis (caps) or sack coats. They hoped someone would identify their remains after the battle. Another 35 years would pass before the subject of identification tags was brought up again.

Spanish-American War

The War with Spain began on April 25, 1898, and again required the United States military to turn their attention to how to identify fallen soldiers. With fighting in Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines, the American Red Cross (founded in 1881) took up the cause to provide identification tags for soldiers. Neither the United States military nor individual states provided any identification tags at that time. The San Francisco Red Cross Society, one of the strongest advocates of tags, furnished them to thousands of soldiers en route to the Philippines. The tags were smaller than a half-dollar and made of aluminium.

The discs were inscribed with the soldier’s company, regiments, and a number corresponding to their eventual Compiled Military Service Record numerical identifier. On the other side of the disc was the visual design of the Red Cross, inscribed with the letters “RED.”

In 1899 United States Army Chaplain Charles C. Pierce was instrumental in establishing the Quartermaster Graves Registration Service. He wrote to the AGO office: “It is better that all men should wear these marks as a military duty than one should fail to be identified.” Pierce, a veteran of the Spanish American War, had witnessed the horrors of war and strongly advocated issuing identification tags for all soldiers in the military. Six more years would pass before the military adopted official tags.

Official Military Tags Introduced

On December 20, 1906, the US Army formally adopted Identification Tags when they issued General Order No. 204. The order read, “An aluminium Identification tag the size of a silver half dollar…stamped with name, rank, company, regiment, or corps of the wearer will be worn by each officer and enlisted man…whenever the field kit is worn.” Each tag had a cord attached through a small hole. The Ordnance Department provided each Army organization and unit with a steel die kit and two sets of dies, one for the alphabet and the other for Arabic numerals.

World War I

Following the entry of the United States into World War I on April 6, 1917, the United States War Department changed regulations on issuing tags. General Order No. 80, issued on June 30, 1917, read, “Gratuitous issues will be limited to two tags to an enlistment.” Soldiers were now issued two matching identification tags. An addendum called, Change of Army Regulations (or CAR) issued with General Order No. 58 on July 6, 1917, added, “These tags are prescribed as part of the uniform and when not worn as directed…will be habitually kept in the possession of the owner”, therefore making the soldier responsible for the care of the tags. They were to be part of their kits and always kept with them.

Another significant change to identification tags was issued with General Order No. 21 on August 13, 1917, when the military added, “The tag now prescribed for wear by officers and enlisted men will be worn also by all civilians attached to these forces.” Civilian employees attached to the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) would be authorized to wear identification tags. One final wartime change occurred on February 12, 1918, with the issuing of General Order No. 27. That order authorized service numbers for enlisted army personnel. The numbers were added to the identification tags.

Identification Tags for other branches

On October 6, 1916, the US Marine Corps issued General Order No 32, which read: “Hereafter identification tags will be issued to all officers and enlisted men of the Marine Corps… always be worn when engaged in field service…at all other times they will either be worn or kept in possession of the owner.” Initially believed to be of little importance, opinions later changed.

On May 12, 1917, the Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels issued General Order No. 294 stating: “The identification tag for officers and enlisted men of the Navy consists of an oval plate Monel metal…and suspended from the neck by a Monel wire encased in a cotton sleeve”. The Navy had more information added to the tags, which read, “The tag has on one side the etched fingerprints of the right index finger…the other side the individual’s initials, surname, month and year of enlistment [in numerals] …this side will also bear the letters U.S.N,” with officers it added: “Initials and surname, rank held, and date of appointment.”

The US Coast Guard issued Identification Tags authorized by the Chief of the Bureau of Navigation in Circular Letter No. 152-41 on December 16, 1941, which read, “The Bureau also directs identification tags be prepared and furnished the officers and enlisted men of the Coast Guard…the letters USCG should be stamped or etched on the face of the tag issued to officers and men of the Coast Guard”. In times of war, the Coast Guard operated under orders of the Navy, and they began to discontinue tags in the 1970s.

Between the World Wars

Following the end of World War I on November 11, 1918, the US Army made very few changes to identification tags until December 1, 1928, with Army Regulations 600-40 stating, “Tags are now officially part of the uniform and must be worn at all times.” From 1906 to 1928, tags were not officially considered part of the uniform. By the mid-1930s, identification tags were referred to by their colloquial name, “dog tags,” and were commonly worn by soldiers, sailors, and marines. The Army Historical Foundation wrote that newspaper editor William Randolph Hearst coined the term to undermine support for President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal. Hearst heard that employees of the newly formed Social Security Administration were issued nameplates for personal identification, and he nicknamed them “dog tags.” There are other rumours of how the nickname emerged, but regardless, the history stretches back for decades.

World War II

In 1940, before the United States entered World War II, a major change was made to tags. Four new types were introduced for use during the war.

The first type came in December 1940 in Army Regulations (AR 600-35). It included a new shape and size and was made of Monel metal. It was two inches long by 1 1/8 inch wide and 1/40 inch in thickness. The tags included five lines of information:

- Name of soldier

- Serial Number and then added the blood type “A”, “B”, “AB” or “O” blood.

- Name of emergency contact

- Street address of contact

- City and State of contact

The second type, introduced in November 1941, made additional changes, including adding the religious affiliation of the wearer on the fifth line. Those designations were C for Catholic, H for Hebrew, and P for Protestant. This presented a challenge for service members who were members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. The church, not considering itself Protestant, requested that the letters “LDS” be included. They contacted the War Department, but the request was not formally adopted. Some soldiers created their own dog tags that included the LDS designation. Thus, the five lines on this tag were:

- Name of soldier

- Serial Number and Tetanus immunization (Letter T and 2-number year and added 2-number year for when toxoid was completed) and also the blood type of the wearer with the following: “A, “B”, “AB”, or “O” type blood.

- Name of emergency contact

- Street address of contact

- City and State of contact/Religious Designation

The third type, introduced in July 1943, cut the lines down to three and included the following modifications:

- Name of soldier (with first name, middle initial, and last name)

- Serial Numbers, Tetanus immunization date, tetanus toxoid date, and blood type abbreviated.

- Religion of wearer (abbreviated)

The fourth type, introduced in March 1944, also included three lines and lasted until April 1946. It was nearly identical to the previous type, but the last name was listed first, followed by the first name, last.

One additional change occurred when a notch was added to one side of the tag. A myth began circulating that the notch was added for medical reasons, to hold open the mouths of deceased soldiers to prevent the body from gaseous bloating. In reality, the notch was created by the stamping machine.

In the years leading up to the Korean War on July 1, 1947, the tags were further modified and began adding prefixes as part of the serial numbers, with “RA” added for Regular Army.

Korean WarDuring the Korean War from 1950-1953, two styles of tags were used. One was for the US Army, and the other for the US Navy. The Army’s tags included these abbreviations:

- Prefix “RA” Regular Army

- Prefix “US” Enlisted Draftee

- Prefix “NG” National Guard

- Prefix “ER” Enlisted Reserve

- Prefix “O” Officer

These prefixes came before and were part of the assigned serial number (RA12345678). There were four lines on this tag, with the fifth left blank:

- Name of soldier

- Serial Number of soldiers, including prefix used for types of service

- Tetanus date and blood type

- Religious preference

The US Navy issued tags with three lines that included:

- Name of sailor

- Serial Number of sailors

- Letters “USN” and religion

Vietnam War

Several variations of identification tags were used during the Vietnam War. The first type, used through 1967, utilized five lines, and tags were no longer notched.

- Surname of soldier

- First name and middle initial

- Prefix and Service Number

- Blood type

- Religious Preference – Could be spelt out instead of abbreviated.

The second type issued during the Vietnam War was used from 1967-1969 with very little change from the previous type. They included:

- Surname of soldier

- First name and initial

- Prefix and Service Number

- Blood type (positive or negative could be listed), and number

- Religious preference – with the word spelt out

The third type used during the Vietnam War had effective use from 1969.

- Surname of soldier

- First name and initial

- Social Security Number

- Blood type – can be shown as negative (neg) or positive (pos).

- Religious preference – with the wording spelt out

During the Vietnam War, the US Marine Corps issued tags during the same period as the Army. The first type used by the USMC was similar to the Army’s.

- Surname of soldier

- First name and initial

- Service Number, or if after 1972, the Social Security Number

- USMC listed, followed by the size of the gas mask worn (S-M-L)

- Religious preference – with the word spelt out

The US Navy also followed a similar style during the Vietnam War.

- Surname of soldier

- First name and middle initial along with blood type (positive or negative could be abbreviated)

- Prefix used and Service Number or Social Security Number after 1972

- Abbreviation of USN listing the branch of service

- Religious preference – with the word spelled out